XR Stage: A New Era in Designing for the Stage

The new era of stage productions

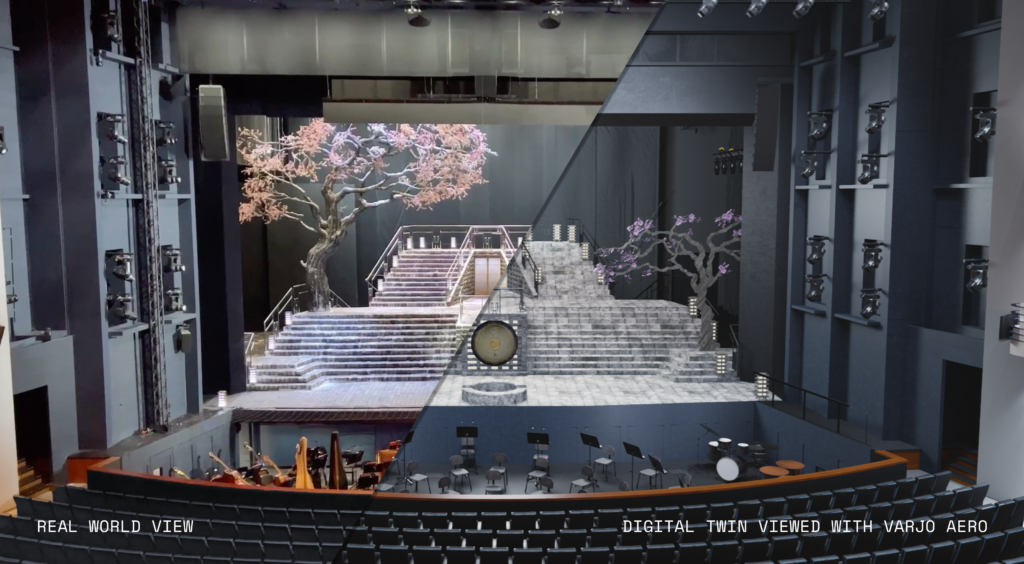

Developed by Finnish National Opera and Ballet, XR Stage is set to transform the world of stage design. This groundbreaking virtual design tool for large-scale stage productions empowers artistic teams to create photorealistic digital twins of any stage set, providing time for testing and experimenting from proof-of-concept onwards.

Beyond streamlining production design, XR Stage opens the door find ways to enhance the audience experience and deliver maximum operational safety.

Why XR Stage?

Throughout history, opera houses have embraced innovation. Creating unforgettable experiences in the 21st century requires new tools and technologies that streamline complex productions. The birth of XR Stage answered a need to address common production challenges. Tight budgets and timelines, along with the often evolving nature of artistic vision, have driven the creation of this platform.

XR Stage enables high-quality visualisation long before production begins and ensures seamless collaboration between different teams, reducing the need for traditional scale models. The product is an open-source platform that is available for any opera house to use.

Learn how XR Stage can enhance your work

With the XR Stage platform, all corners of opera and ballet houses can benefit from unlimited stage time, better preparedness, improved efficiency, and more seamless collaboration. It offers a solution to minimize risk and enhance creativity.

Click on the roles below to learn more precisely how you can benefit from the use of XR Stage platform. (clicking on the role will open up a dropdown menu).

- Effortless proof-of-concept: Test new productions risk-free before committing.

- Fuel creativity: Gain inspiration from the virtual stage during artistic design.

- Easy communications: Collaborate globally in a true-to-life virtual environment.

- Minimize errors: Visualize and test concepts early on, reducing misinterpretation.

- Unlimited stage time: Familiarize performers with the set in advance.

- Enhanced work safety: Improve physical stage safety through immersive practice.

- Unlimited stage time: Test and experiment without assembly, reducing production costs.

- Streamlined design: Visualize sets realistically, speeding up construction.

- Seamless collaboration: Work with artistic teams remotely in real-time.

- Saved time: Reduce travel with real-time visualizations.

- Reduced waste: Accurate plans minimize unnecessary set construction and final-stage modifications.

- Simplified rehearsals: Sketch, test, pre-program technology, and run through changes, resulting in efficient rehearsals.

- Effortless proof-of-concept: Test new productions risk-free before committing.

- Reduced costs: Cut down material and labor costs by trying them out virtually beforehand.

- Enhanced work safety: Improve physical stage safety through immersive practice.

- Leading technical development: Explore virtualization’s potential in live performances for long-term growth.

- Effortless proof-of-concept: Test new productions on your own stage risk-free before committing.

- Streamlined communication: Ensure everyone, regardless of location, can access the virtual model at any time, keeping everyone updated on shared productions.

- Seamless collaboration: Collaborate globally in a true-to-life virtual environment.

- Minimize errors: Visualize and test concepts early on, reducing misinterpretation.

- Unlimited stage time: Familiarize performers with the set in advance.

- Enhanced work safety: Improve physical stage safety through immersive practice.

Get started with XR Stage

Unlocking XR Stage for your opera house is straightforward and cost-effective. The concept is open-source and available for any opera house to use. Here is how it works:

- Connect with the Finnish National Opera and Ballet: Reach out to us for step-by-step guidance on kickstarting your XR Stage journey. No high-tech requirements, a laptop is all you need to get started.

- Select your contractors: Find the right professionals to create a 3D model of your space and stage. Your contractors will ensure seamless integration with the game engine.

- Virtual stage modeling: Collaborate with your chosen contractor to adapt the stage for the 3D environment and game engine. Materials and functions will be created within the game engine.

- Virtual stage development: Once the virtual stage is ready, begin developing essential functionalities within the platform. Start small and expand gradually as needed.

- Implement the virtual stage into your operations: Now you can start collaborating with different teams and get a stage production started.

- Collaborate and develop: Join our network of opera houses to exchange insights and co-develop future productions using the XR Stage platform.

See what it looks like

Learn how the XR Stage platform has streamlined the process of creating world-class stage productions around the world.

The video content can only be played if you have accepted targeting cookies. To modify your cookie settings, go to cookie settings at the bottom of the page.

Case Turandot – Finnish Natinal Opera and Ballet

Questions? Find the answer!

A laptop is all you need to get started. The platform runs on a game engine, and it can be used on VR headsets but also desktop and mobile.

The initial cost is low. The concept is an open-source platform that is free to use. You only need a contractor to create a 3D model of your space and stage.

Yes. The more opera houses use the XR Stage concept, the easier it is for everyone to create co-productions and rental pieces, exchange insights, and co-develop future productions using the XR Stage platform. Together, we shape the future of stage design!

No technical expertise is required to use the platform.

XR Stage can be used also for existing productions. When you have a virtual model of your stage, you can implement all the elements into the platform and enhance the production. XR Stage is also highly effective when an existing production goes on a tour.

We’re here to help you!

Ready to revolutionize your stage production? Contact:

External Relations Manager Lauri Pokkinen (lauri.pokkinen(at)opera.fi / +358 44 2627 699)

Project Manager Hannu Järvensivu (hannu.jarvensivu(at)opera.fi)

Production and Technical Director Timo Tuovila (timo.tuovila(at)opera.fi / +359 9 4030 2201)

Webinar: A New Era in Designing for the Stage 7.11.2023

For more information contact:

Project Manager Hannu Järvensivu (hannu.jarvensivu(at)opera.fi)

Production and Technical Director Timo Tuovila (timo.tuovila(at)opera.fi)

in collaboration with